You can take the northerners out of the north – it’s now 2022

You can take the northerners out of the north, but you can’t take the north out of the northerners. It’s somewhat of a cliche, but for some unexplained reason, we human beings love cliches – which is why the news media love to annoy us with constant cliches in all their news broadcasts. Perhaps cliches give us a sense of comfortable familiarity. We remember them, groan over them, and secretly, perhaps, pat ourselves on the back because we know them so well. But at the end of the day, we appreciate them because they are true.

My wife and I come from the north. My sister would disagree, but then she lives in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. But like myself, and my wife, she was born in northern BC.

I was born in a little place called Hazelton. It originally gained its importance to European prospectors, outfitters, and settlers as being the head of navigation on the Skeena River above Port Essington. At one time, Port Essington was a booming port and cannery town at the mouth of the Skeena River, well on its way to being the city its founders dreamed of. But that all ended with the railway on the other side of the river with its terminus at the planned City of Prince Rupert, which boasts the third largest natural harbor in the world. But I digress…

When I was born, my parents owned a half section on the Skeena River in Kispiox Valley. In those days, right at the end of the 1950s, telephone had just come to the valley and electricity was not even close.

Our telephone was a rectangular wooden box mounted on the wall in the kitchen. It had a key to open the face of it, so that we could replace the bank of dry-cell batteries housed inside. They were necessary to power the phone. Unlike today’s phones, each phone had to be powered onsite, and the wires that carried our voices over the miles were galvanized overhead wires reminiscent of the telegraph wires that ran along the railroad lines.

A big heavy receiver hung on the side of the box, a big bakelite-coated monstrosity that could have made a dangerous weapon. Then there was a crank handle sticking out the same side.

Our number was 92M, which translated to a long and a short – that is – a long crank and a short crank. But apart from a small number of local friends, knowing how to translate the numbers they gave us was something we left to the operators. You would pick up the phone, politely ask, “Line busy?” Then if all was silent, you would give a good long crank and the operator would pickup. You would give the operator the number you wanted and she would dial it. I don’t recall ever talking to a male operator.

We had neither running water, nor indoor plumbing. Waste water from cooking, washing dishes, brushing teeth, etc., was carried out in a bucket and unceremoniously dumped over the fence into the pasture. A lot of potatoes used to come up there every year, which we never harvested…

There was a little closet for another bucket with a seat and a vent out through the wall. That one was mainly for guests and emergencies. That bucket had to be carried all the way across the pasture to a pit. For the rest of us, there was a rustic wooden hut out between the orchard and the forest, which was no end of creepy after dark. And it was ridiculously cold in the winter. No one wanted to be first on winter mornings!

Water came into the house from the well via a pump on the pantry wall, which we used to pump water into a 45 gallon drum mounted on top of the ice chest. It was plumbed to the one sink in the house which drained into a grey well behind the house.

Our bathtub was shaped like any modern bathtub, except that it was galvanized and it hung on a nail behind the house. We would heat up the water in galvanized laundry tubs on the wood stove, then pour it into the bathtub sitting on the kitchen floor in front of the stove.

All the kids bathed in the same water. As it cooled down, Mom would add more hot water. The worst part of bathing this way was that when it was 40 below zero outside, the metal on the tub was still terrifyingly cold by the time you got into it if you were the first one in!

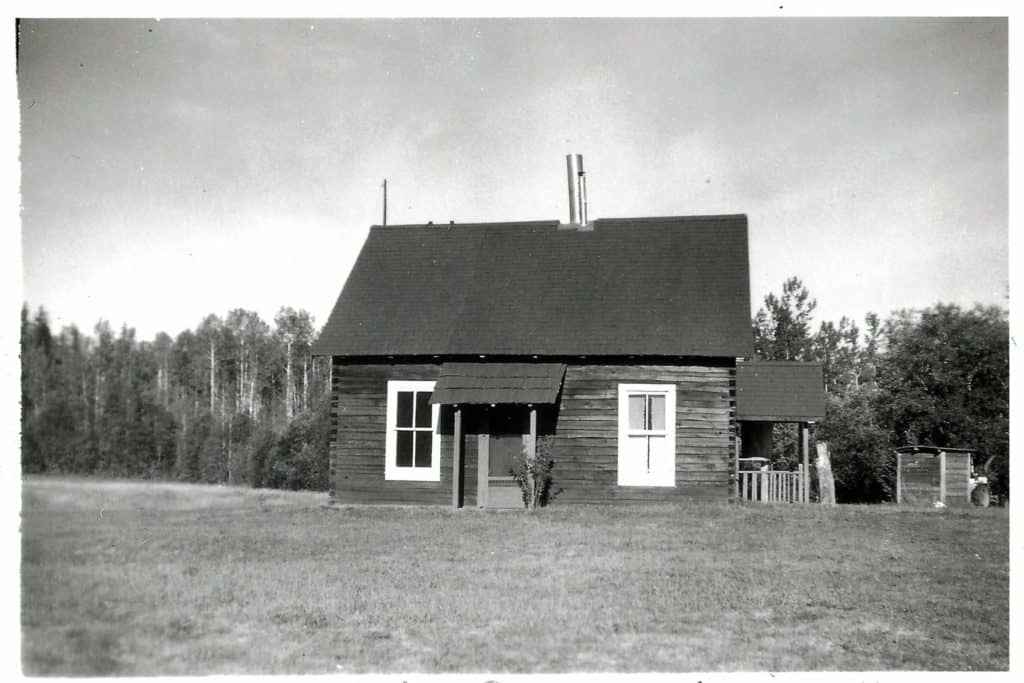

Also in the winter, it got very cold in the house at night. The house was a log structure built in the 1860s. It was beautifully built, with hand-squared logs and dove-tail corners. Typical of its day, the windows were tall, double-hung windows, which was great for letting in light, but not so great for holding in heat. Worse, there was not even a hint of insulation in the roof. There was wall-papered cardboard attached to the rafters, then shingles.

So, it took a lot to heat the house, and even fully stoked before bed, the fires would go out at night. We slept under a lot of blankets, which is why, even to this day, I tend to sleep a lot better with extra weight laying over me. Because in the morning when we got up, when outside temperatures dipped down as they always did for several months over the winter, there would be a skim of ice on the water and the milk on the counter in the morning.

The house was heated with wood – a lot of wood! We cooked with wood all year round, a relied on it to keep us warm in winter. We used the wood cookstove for heating, as well as a big Ashley Wood-Burner in the front room when it got colder. I used to reach out from under the covers on cold winter mornings to see if the Selkirk insulated chimney was getting warm before I attempted to get out of bed!

Living as we did was not a problem for any of us as kids. It’s what we knew. It was normal to us. But it must have been something for my mom, who grew up in a small village in Ontario and had become used to living with electricity, running water, and indoor plumbing. But if it was an issue, she never let on to us.

But living as we all did in that country, everybody had to pull their weight. Kids did things most people just don’t think of kids doing these days. From about the time I started school, my job was to split the firewood every day, and my slightly younger brother’s job to bring it to the house. We collected eggs, carried water for the animals, spread out the hay Dad dropped, etc. Come haying season, I was on the tractor from the time I was seven. It was common for young kids to drive tractor in that country, while the bigger, stronger kids and adults handled the heavy lifting. Again, it was our normal.

There was a lot of time when we could play and explore, too. I spent a lot of time exploring animal trails, picking berries and hazelnuts, snaring rabbits, snowshoeing, fishing, and much more. I even built several cabins, because nobody ever told me anything was too difficult for a kid. Imagine my surprise years later when I discovered someone was living in one of the cabins I built when I was 11 or 12! I doubt it’s there any more.

My wife grew up quite differently, having grown up in the City of Prince Rupert, as they call it. Our lives couldn’t have been more different in many ways.

But one thing is the same – we both grew up in the north.

In the north, there are few communities, they are much smaller, and there are often hundreds of miles (kilometers) in between. There is great ethnic diversity in the north, but the north is also an amazing melting pot, meaning that people tend to figure out fairly quickly how to get along and how to socialize with one another. There are fences in the north, but they are usually used to keep animals in, not to keep people from getting to know one another. Fences between houses in the towns and villages, if they exist, are more for decoration and rarely will you see a fence you can’t see over.

But in the south, you can live next door to someone for years and never get to know them. You can try, but there are many people living side by side who just want to be left alone and never want to have anything to do with their neighbors. I will never get used to that.

In the north, if you knock on someone’s door, you will probably hear someone yell out, “Come in!” In the south, you have to make an appointment to visit just about anyone.

You can take the northerner out of the north, but you can’t take the north out of the northerner.

I miss the north. It is still my home.